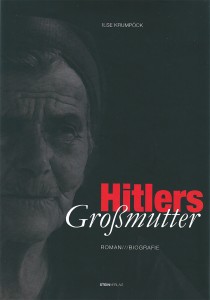

Hitlers Großmutter

Hitlers Großmutter

Romanbiografie, Steinverlag, Bad Traunstein 2011.

„Es war nicht Graz, sondern Wetzlas.

Nicht Graz in der fernen Steiermark,

sondern Schloss Wetzlas bei uns im Waldviertel.

Und er hat auch nicht Frankenberger geheißen, sondern …“

Die Geschichte der armen Anna Maria Schickelgruber und ihres „uneheleiblichen“ Sohnes Aloys basiert auf einer sehr naheliegenden Theorie, von der die Autorin selbst überzeugt ist. Die Lebensgeschichte der Großmutter Hitlers ist in einem Roman verpackt, der die Biografie dieser Köchin in einer schlichten Dienstbotensprache widerspiegelt.

Im inneren Monolog schildert die Magd unter anderem ihr folgenschweres Schicksal auf Schloss Wetzlas und den anderen Kamptalschlössern bei ihrem jüdischen, zum katholischen Glauben konvertierten Dienstherrn Heinrich Freiherrn von Pereira-Arnstein und dessen Sohn Adolf, das in die Sozialgeschichte des Waldviertels um 1830 eingebettet wird. Die fiktiven Erlebnisse einer Schicksals bedingt moralisch geschädigten Köchin, deren Judenhass sich schließlich auf ihre Nachkommen vererbt, werden mit tatsächlichen Begebenheiten und Quellen vermengt, die – eigens ausgewiesen – durch fundierte Belege im Anhang nachvollziehbar sind, womit das Motto der Autorin für ihre Bücher „Jedes zweite Wort ist wahr“ seine Berechtigung erhält.

Dem Leser bleibt es vorbehalten, sich seine eigene Meinung über die Herkunft Hitlers und seine Waldviertler Verwandschaft zu bilden. Ebenso zur neuen Theorie Krumpöcks, deren Wahrheitsgehalt vielleicht sogar einem DNA-Vergleich gelassen entgegen blicken könnte, an dem der Autorin jedoch nichts liegt.

English

Ilse Krumpöck

Hitlers Grandmother

In Ilse Krumpöck’s richly researched novel-biography of Hitler’s grandmother, Anna-Maria Schickelgruber, the first-person narrator tells her story from beyond the grave, and is eager to put right historians who have hitherto located the shame of her seduction in far-away Styria, rather than in the Waldviertel area of Austria where the author and her publishers are based.

In her opening words she reveals that it was not Graz, as historians have surmised, but Wetzlas in the Waldviertel, and the seducer’s name was not Frankenberger, as some have suggested, but Adolf von Pereira Arnstein, son of Aaron and Judith, baptised as Heinrich and Henriette. It was Klara, Hitler’s mother, who discovered this, and kept it quiet, before calling their own child after his grandfather, in the Germanic tradition. Hans Frank, Hitler’s lawyer, invented a Jew called Frankenberger to throw future historians off the scent. No cook called Schickelgruber has been found in Styria’s chronicles.

Schickelgruber records her tale, and her origins in the Waldviertel, and was by no means the ‘well-to-do’ cook of Nazi mythology. Her early days were grindingly poor – so much so that the painted wardrobe in the museum at Horn near Döllersheim, which is said to have been among her belongings, could not possibly have been in her possession.

So she was born in Strones, and records show that she later married Georg Hiedler, and is thus Hitler’s real grandmother. Strones, she points out, was later destroyed on Hitler’s orders, to make way for a Wehrmacht training ground. She surmises that he did this in order to erase all traces of his true origins.

She details the cycles of the peasant year, of the yearly rituals of sowing and haymaking. Her parents want to see her married, but few suitors come. After her mother died when she was 26 she is often called to her father’s bedroom to satisfy his needs, and there is nothing she can do about it.

In need of a job, she finds herself visiting a nearby castle – on the way being alarmed by some statues of ugly Jews by one Johann Baptist Wanscher from Linz – never in her life encountered such opulence. There are strange figures around – a dwarf, some strange peasants – and she is grateful to be bathed by a maid. She becomes a cook at the castle, learning to smoke the trout fished from the nearby rivers. At a soirée in the castle (Schloss Greillenstein) at which she meets the count and countess, she also first encounters Baron Pereira-Arnstein, who is in a fury about the hatred currently being directed against Jews. The Countess suggests that he might be exaggerating, but his rage is unabated.

Anna Maria’s curiosity is piqued, and she tries to find out more about the wealthy Pereira-Arnsteins, a cultured and verx rich Jewish family who have had themselves baptised. (Five castles in the Waldviertel were in her possession). Meanwhile, Anna Maria continues working as a valued cook in the Castle learns to read and write and is valued for her pastries. No longer working in the fields, she also becomes more attractive than before.

One evening Baron Pereira-Arnstein compliments her in person on her desserts, and she notices that he is particularly handsome (she refers to him as “the Jew”). She learns that she is to leave Schloss Greillenstein to go and live with the Jewish Baron in Schloss Wetzlas. She feels shocked and betrayed.

Once there, however, she learns to cook kosher food and discovers the rites and rituals of Jewish life. She also falls in love with the almond-eyed Baron who, despite her sometimes rather attempts to attract his attention, fails to notice her. She earns some extra money on the side as an abortionist, or ‘angel-maker’, as they are known.

After the Baron’s death, his feckless son Adolf, having married a plump Jewish girl, turns his attentions to Anna Maria, not least on the grounds that she is ‘slim’, and forces himself on her in the observatory from Wetzlas . Of course he immediately dismisses her from his service. She swears to take revenge on him and, implicitly, on his kind as soon as she is able. She is now in her early forties, far from young, and pregnant, and her hopes of becoming a ‘famous cook’ have been dashed. She makes her way, slowly, back to Strones – reminding the reader that the village has since been razed to the ground by Hitler’s tanks. She is taken into service by the mayor and his wife, but this time she is paid nothing.

She has terrible birth pangs, and when she prays that they will come to an end they do: she reflects that ‘the Crucified probably hated the Hebrews as much as I did’. There being no alternative perspective, the reader is trapped in the mind of a 19th-century anti-Semite, which is a far from comfortable place to be.

Once she has given birth to Aloys, the mayor’s house is also uncomfortable now, as her son makes a great deal of noise, but she stays with the mayor and his family for a total of four years until the arrival of miller’s journeyman the drunkard Georg Hiedler in the village – although the Nazis will later bring him there a good nine months earlier to ensure that Hitler has an Aryan father. Georg is horrible to the child, who is eventually given away. To her surprise, Anna is recalled to the Pereira- Arnsteins in Schloss Allentsteig to cook for Adolf’s brother, who is now in charge. The Countess says, however, that she must return to her husband Georg to check that he is happy with the idea.

She continues to cook for the countess, but further develops her feelings of rage and revenge against these wealthy, idle people. She spits in the children’s food, and adds so much salt that it is unpalatable. Her fantasies are poisonous, and indeed begins to poison the Jewish Countess and her family by adding arsenic to their cheese dumplings. They develop severe stomach pains and diarrhoea. Anna, on the other hand, feels triumphant.

She herself falls ill with pneumonia, much to the discomfiture of her husband Georg, who laments that no more money will come into the household. She is given a Christian burial.

Aloys never forgives his stepfather for refusing to adopt him, and is brought up by Georg’s brother Johann in the village of Spital near Weitra. He knows very well that he is part Jewish, and feels this to be a ‘stain’. He trains as a shoemaker at the age of 15 – not 13, as the history books have it – and is highly ambitious. Anna questions the accuracy of the dates and figures in the Döllersheim registry, in which Georg is posthumously recorded as the legitimate father of Aloys. Aloys is filled with self-loathing in a time of mounting anti-Semitism, not least under Vienna’s virulently anti-Semitic mayor, Karl Lueger. That same self-loathing will be passed on to Aloys and Klara’s surviving son, who will take his revenge in the insanity of the Third Reich.

Hitler’s Grandmother is a grim tale full of impressive local historical research into the connections between Hitler’s ancestors and the communities of the Waldviertel area of Austria, and one which imaginatively – and gruesomely – inhabits the mind of a woman very much of her time and place, with all that that entails.

The first 6000 characters from the book:

‘It wasn’t Graz, it was Wetzlas. Not Graz in far-off Styria, but Wetzlas Castle here in the Waldviertel. And his name wasn’t Frankenberger, either, it was Pereira-Arnstein, as none of those snoopers would have guessed. But that’s to stay my secret. For ever. And I’m still proud of that. I’ve never given it away, even though they all tried to force me. Not even Adolf and his henchmen found it out. And he was the one named after his grandfather, Aloys’s real father. After him, after Baron Adolf von Pereira-Arnstein, from the only Jewish family far and wide. Except that the noble Baron’s father, Heinrich, switched to the enemy camp, from the Mosaic to the Christian, you might say. From Moses to the Messiah, if you like. They had themselves baptised, he and his wife Henriette, in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost, Amen. Just to get into the noblest circles! And all at once the doors of high society were open to them. If you ask me, they just hung their flag in the wind and let it flap from the Old Testament to the New. In fact their names were Aaron and Judith, not Heinrich and Henriette. Later on, no one thought it odd that they called one of their sons ‘Adolf’. Not even my grandson’s keenest sleuths. Only Klara, Hitler’s mother, saw through it one day in 1888. But she and Aloys kept it to themselves, for good reason, and didn’t breathe a word. And then they called their fourth child “Adolf” too. After the grandfather, in the Germanic tradition. Except that he had spoken Yiddish in his day. In nomine patris et filii et spiritus sancti, Amen.

And if I’m writing it down at long last, it’s just to remind myself what it was really like. Very well, if every one of God’s children after his demise combines the ever-present wisdom of the Creator with the humble knowledge of humankind and I must no longer express myself like some stupid country creature, if for once and all I write the truth from all my soul:

In fact he deliberately put them on quite the wrong track, did good Doctor Frank. He just hoped for a more lenient sentence in Nuremberg, with his deceitful tale. 21 days before they hanged him, he wrote it down and seriously believed he would be saved from the noose at the very last minute. And yet he was Hitler’s lawyer and his best hangman in Poland. A thousand and ninety-one pages he scribbled full in his cell. With impeccable handwriting so that his children could be proud of him. Of him, the feared ‘Jew-butcher of Cracow’. But sadly nothing came of it, as I know today. They weren’t interested in his forked-tongued yarn, although it was meant for their eyes. But the fact that from the last line on page seven hundred and ninety-nine he speaks of ‘certain circumstances’ in our family tree has kept all the snoops busy for ages now.

William Patrick, my resourceful great grandson, was the one who blackmailed Hitler then. He sat down hard with the excitement, my grandson did, when he had that letter in front of him. I can still see him as if it was yesterday, and him sweating with fear. His hands were shaking, pale as death he was, before he called Frank in. At the time I thought that was it! But his lawyer could give him nothing solid, only gossip and gobbledygook. The stone that fell from my heart must have been as heavy as a Waldviertel boulder, that those ‘certain circumstances’ didn’t come to light.

But everything that Frank came up with was an outrage. He lied deliberately, he did, that guileful swine! Just to make them look for a Jew called ‘Frankenberger’. And that’s exactly what they went off and did. But there was no Frankenberger at the time in question. Certainly not a Jewish one. No wonder, when I got pregnant, there hadn’t been a single Hebrew in the whole of Styria. And neither has a cook called ‘Schickelgruber’ been traced either in the messenger book or in the Graz register. Frank pulled a wicked prank on them all! And he served up a few more lies, too, that vile rogue: first of all, my husband, Georg, was never called ‘Herr Hitler’, it was ‘Hiedler’ or ‘Hüttler’, and secondly I wasn’t from ‘Leonding near Linz’, but from Strones near Döllersheim in the Waldviertel! So, fair’s fair! That on its own should have given the sleuths pause. Leonding wasn’t my place of birth, it was the resting place of Aloys, my son! And he wasn’t only 14 either, he was almost 40, when he changed his name from ‘Schickelgruber’ to ‘Hitler’. He must have misheard that one, Frank must, when he was spying on my boy and me. And besides, I didn’t ‘give birth’ to Aloys at my Jewish master’s house, but at the home of Mayor Trummelschlager in Strones. Lies after lies! Of course the whole thing didn’t happen ‘in the late 60s’, but in the 30s of my own century. All the things that fellow dreamed up in his cell. And by the way! What’s the meaning of ‘Frankenberger (or something similar)’? If I hear that one more time! And of course that lets him neatly off the hook, the Generalgoverneur, because he didn’t want to commit himself. Writing such nonsense as a lawyer is the worst thing in the world! Only a sick brain could come up with such a thing. I was even supposed to have corresponded with my Jewish employer, the ‘Polish butcher’ claimed. What balderdash! And certainly not for nursing money for my Aloys. Such perfidy!

I learned to write with difficulty, I admit, although hardly any of the ordinary people could in those days. Certainly not such a poor person as I was! And of course there was communication between the young Herr Baron and myself, but certainly no written communication, let alone ‘hushed-up common knowledge’ that Aloys had been fathered under ‘circumstances compelling the payment of maintenance’, as that villain loftily put it. In my day fathers never had to pay maintenance for their illegitimate children. That so few peopled doubted it! He must have got it mixed up with something else, the idiot, and all the other clever-clogs copied it off him after. Incredible! And one more thing: they couldn’t even count, those pests! It can’t be the case that the Jew paid me nursing money until Aloys was 14, because his son supposedly got me pregnant, as Frank tried to persuade everybody. I’d been in the grave for four years by then! My son was ten when I died, you’ve got to know that. It would make you want to thump your head against the wall, all that stupidity. Never would a fine gentleman have gone on making payments of his own free will, after the death of his son’s below-stairs dalliance. Never, ever! And then there’s the fact that Heinrich died not long after the boy was born. How was he supposed to have paid for his misbegotten son? And last of all, I’ve never named a father for the child, certainly not one who was ‘capable of paying’, as they put it. The infamy of it! It would have been nice if it had been the case. So, as I’ve said – all a pack of filthy lies! Slander!

Of course that devil’s advocate, that man Frank, was loyal unto death and pulled the wool over all their eyes when, shortly before his execution, he wrote down the supposed truth about my grandson. That hypocrite gave the prison chaplain his shoddy effort for the monastery archive, before they hanged him. But it’s not there any more, as far as I know, it’s in the memorial for the murder of the Jews in Israel, where it belongs. But because Frank’s grasping wife had a nice and tidy typed-up version of that web of lies copied out after the war, all the snoopers soon started parroting all that hand-me-down nonsense. From then on all the untruths were hammered into people’s heads, as you can imagine. But the truth never came to light. And that’s the way it should be. Because it meant they never tracked down who Hitler’s grandfather really was, the grandfather of that mass-murdering brute, my shame as I lie here in my grave in Döllersheim.

Wetzlas here in the Waldviertel, not Graz in far-away Styria, that’s where it was. It hasn’t occurred to most of the spies that I could never have got as far as Graz on foot as a poor peasant girl. And people like us hardly ever travelled by train or coach. No, all those eager history professors and beetling local historians copied off each other and all them, like trained monkeys, followed the wrong trail, which even caused confusion in the universities. And the solution was so obvious! I was supposed to have been in service as a cook in Graz, poor Anna Maria Hiedler, née Schickelgruber! And how could that have happened? I’ve never been out of the Waldviertel in my life!

Still others have claimed I was in service with the Rothschilds in Vienna, and Salomon Meyer got me with child. And then he threw me out of the house when I was pregnant. Such vile behaviour! Although – thinking about it, that one’s possibly not so wide of the mark. In my day the Rothschilds were high up in the banking business and, like the Pereira-Arnsteins, they had their fingers in all sorts of pies. They were Jews, of course, those five brothers, and all made barons because of their wealth. Just like our own aristocrats, in fact. To that extent there was a grain of truth in it. Except that the family was the wrong one, and never had anything to do with the Waldviertel.

But other horrible tales have been told about me too. Some clever people have even claimed they knew that a ‘parental inheritance’ had been left me in a will, and that the interest payments were recorded for years in the district court in Allentsteig. All completely far fetched! Nothing but lies and fiddle-faddle! Whether you believe it or not: there was never any will, I swear! And no interest payments either. I should know that if anyone does! Yes, yes, he did pay, Adolf did, my baron, that’s true, but not maintenance money. And it wasn’t the father, Heinrich, who had to pay, but his incontinent son, paying for his own sin. The rumour of the inheritance lingered stubbornly on because of the little bit of interest that I got from my savings that I’d put into Leopold Wagner’s ribbon factory in Sieghart’s General Bank. Yes, that’s the truth! But most of this mysterious ‘legacy’ was hush money, you should know that, because I blackmailed the noble Herr Baron. Over Aloys, obviously, out of revenge! And when my noble Baron learned at the age of 42 that I had married Georg, he didn’t send me a single penny after that! On the contrary! He sold Wetzlas Castle that same year and off he went with his family. Just so that his ‘Schickse’ wouldn’t come after him! What a coward! He wasn’t even single, as everybody said, he was married, it’s important to know that. Except he didn’t wed her at the altar, it was under a baldachin in the castle grounds, in the Hebrew style. At any rate that was the end of my extra monthly income. Nothing was found in writing, after Hitler had Döllersheim wiped off the map. He did a good piece of work there, that fine grandson of mine!

They scouted everything out during the war. They were quite meticulous about it. After all, it was about his family tree, their ‘Führer’s’ family tree! He, who demanded that everyone had ‘kosher’ forefathers before killing everyone who really had kosher ones, couldn’t have proved his own Aryan descent! They all went snooping around in our family history. They went after my secret like vultures, because they scented Jewish blood in their idol. Rightly, of course. One Frank – Karl Friedrich, the other one – the lawyer, Rudolf Koppensteiner – the genealogist, Heinrich Himmler – the head of the State Police and whatever all their names were. You can’t imagine what would have happened if the Reichsführer SS and his Gestapo had happened n my secret in the middle of the war. And yet it’s a mystery to me why they didn’t.

But thank God those rogues found nothing, because they were poking their noses around in the manor houses. That’s where most of his own devotees were. And even after the war the sleuths didn’t dig up anything useful, because the explanation would have been too easy. Too easy for the ‘greatest general of all time’. Don’t make me laugh! What really happened is a long story, which I’d like to put on the record now. And one thing it a time, albeit back to front, because time has lost all meaning for me since I asked for forgiveness at my final unction, and the Almighty forgave me all my deadly sins:

Anna Maria

I died 164 years ago. The day after Epiphany, in the middle of the Waldviertel winter. That’s me,

‘Hielder Manna, wife of Hiedler Georg, owner of Klein-Motten No. 4, legitimate daughter of Johann Schicklgruber, formerly farmer in Stronnes, and Theresia, née Pfeisinger von Dietrichs.’

The snow lay several feet thick, blown by an icy wind over the barren fields and frozen streams, when I was buried. ‘Emaciation as the result of pulmonary tuberculosis’ whisked me away on 7 January 1847, as our pastor, Reverend Oppolzer, neatly recorded in Döllersheim death registry. He gave my age as 50, even though I was two years older than that. People weren’t so precise in those days, you have to remember. And he wrote ‘Schicklgruber’ and ‘Stronnes’, which wasn’t unusual in those days either. On the same page in which he recorded the deaths of the two foundling children who, like many others in our Waldviertel, had been taken into care and didn’t make it beyond the age of two. ‘Maria Stockhammer’, No. 5487/84b at the Vienna Birth and Foundlings Institute, who died, according to the register, of whooping cough, and Karl Schaubauer, No. 5987/84b, who didn’t survive measles. A short life was also reserved for the two other children on that page in the death registry, Magdalena Lüngel and Maria Stöcker from Döllersheim. One girl lived to the age of four, the other only six months. They all had some kind of spasmodic or convulsive coughing in those days, the children in the Waldviertel. And the adults dropped like flies from consumption. More or less everybody here had to do battle with throat catarrh, pneumonia and pleurisy, particularly if you were as poor as we were and couldn’t afford wood to heat the house. And in such a heavily forested area as ours, which belonged to the gentry up at Waldreichs.

As the name suggests, the area was rich in forests, but the wood in the Waldmark belonged not to us, but to the lord of the manor. On the contrary, the mechanical work that we had to do for him, manually, on foot or by cart, and because of the fragmentation of the land because of all the children, many of the farmers around our way were up to their ears in debt. If one of them inherited a small something, like my forefather, the widower Jakob Schicklgruber, in most cases nothing remains of it. One half of the modest fortune of his late wife, Eva Maria Sillipin, ate up half the debts, and he had to set aside the rest in the office of Waldreichs Castle, for the inheritance contract in which it says:

‘Of the other half his lordship is owed deposit, inventory tax, office tax, enclosure tax, signature, contract, witness fee for the judge.’

Many of us were poor and ill in those days. As I’ve said already, I suffered, like most of those doomed to die in our district, from consumption of the chest. Most of the cleverer doctors wrote that on the death certificates if they couldn’t hear the snuffles of their emaciated patients with their listening devices and, as in my case, assumed that water had accumulated between the lung and the pleura. That was often the case when the heart stopped doing its job, or when someone didn’t get back on his feet after a stroke, like Vinzenz Pöll, for example, the businessman from Döllersheim just below me in the death register. He only lived to the age of 47. Poverty was to blame, all that mechanical work, bad food and the terrible cold. You had to be strong and work hard if you wanted to survive, because the winter is so terribly long in the Waldviertel.

But even the better kind of people often died of pleurisy in those days, even if they didn’t live in our district. There was some justice in that at least. Not that we knew anything about them. Most of us only knew the people from the village, perhaps a few from the little nearby village of Döllersheim. The larger towns like Zwettl, Krems, Horn or Weitra were too far away for us ever to see them. I was the only one from our village who later got to Kirchberg am Walde. A cook from the neighbouring village even made it all the way to Vienna. But that was the exception. And because we didn’t know much about the world, we didn’t know anything about the noble houses who thought they were called ‘by God’s mercy’ to decide our fates. Today, of course, I know everything about them. The second wife of Napoleon, for example, Marie Louise, who was a daughter of our then Kaiser Franz, die of the same illness and in the same years me. Like most people our age, she had no teeth by then, and was even three years younger than me when she had to say goodbye to the world. Her son, the poor Duke of Reichstatt, the one she had with Napoleon, also died young of consumption. At 21! He had to join in with all kinds of manoeuvres, even though he had a weak chest. After all, he was the son of the enemy and nobody at court would let him forget it. But in my day we had no idea about world history.

In the tiny village of Klein-Motten, which consisted of only ten houses and belonged to the parish of St Peter and Paul in Döllersheim, I bade my goodbyes to the temporal world. Ten houses and a chapel the village had, on the road to Franzen. We lived on the little plot of land up on the plain bounded to the north by a little chain of hills, at No. 4, Georg Hiedler and me. The farm was a bit up from the village stream which rose from its source in Heinrichs’ limestone mountain and flowed gently past our houses to enter the Zieringser Pond. Even though it was quite a sizeable property with a lot of windows, which might have led strangers to think there was considerable affluence inside, Georg and I suffered the most awful hunger. The farmhouse we were allowed to move into soon after our wedding, because we could no longer bear it at home in Strones, didn’t in fact belong to us. It belonged to our cousins, the Sillips or Sillipps, as they sometimes spelled it. Not only did not a single tree belong to us, in all those dense forests full of firs, pines and beeches; we didn’t own a single plant of all the rye, the clover, the oats, the potatoes that grew in the fields that rose to the slopes of the Kamp. We had to share our stony front garden, and we were allowed the previous year’s rotten potatoes. We didn’t even have a cow. Only the goats, three geese and some chickens. If I hadn’t had the spinning wheel that I inherited from my mother, we’d have been even worse off than we already were. There was only ever any money in the house when my fine husband, that rogue, found work in one of the mills. The Gföhls, Granser or the Fürnkranz mill: they never needed a miller, they wouldn’t even take him on as a day labourer. We just had enough to survive – by the skin of our teeth. And yet – I lived to 52, even though we were as poor as the poorest church mice, so much so that had to sell our iron bedstead long before I passed away.

Later the Nazis tried to tell the people that I’d been a ‘well-to-do’ cook. Me – well to do! Trash like me! They told everyone I’d owned a painted linen cupboard, for example. It had ended up in Munich before being brought back to the Waldviertel and placed in the parlour of District Farmers’ leader Ernst Mader in Horn, so that everyone could see it. Such boundless impertinence! Painted peasant cupboards were the purest luxury in my day. I could never, ever have afforded such a thing! Master carpenter Raffloer in Gars treasured and made the cupboard that now stands in the storeroom in Horn Museum. In his day Raffloer provided a clumsy description, with drawings, of what was supposed to be my ‘wardrobe and linen cupboard’. Amongst other things he maintained:

‘Many similar items of furniture from this time were not made with such care as this chest. Even the lock is an original piece of craftsmanship.’

And he ended his interminable eulogy, as if it was my reliquary, with:

‘Gars am Kamp, 21 May 1939. Heil Hitler! Heinrich Raffloer.’

He took such trouble, that master carpenter. And now let me tell you what it was really like: the cupboard comes from Strones, and it was probably made before my day, but it never belonged to me! In fact, it used to stand at ‘No. 13 Strones’ where Mayor Trummelschlager lived and I was allowed to give birth to Aloys, but I didn’t own a thing in that place! Why would I have done? I was only there as a serving-girl with my little bastard. The later owners of 13 Strones, Johann Weissinger and his wife Maria, who lived there in the first year of the war, stoutly maintained to District Farmers’ Leader Mader that it was a wardrobe from the property of the ‘father of our Führer and Chancellor Adolf Hitler’, which is to say that Aloys inherited it from me. Everyone testified as much to notary Max Bernhauer in Horn, owner of No. 17 in Strones, Johann Lainer, the owner of No. 11, Franz Waldhausen, in fact even mayor Franz Weber and the Heinrichs’ councillor, Gottfrie Krapfenbauer. As I’ve said, they’d probably have liked to turn the old laundry cupboard into a tabernacle for the altar of their new ‘Christ’. And the wardrobe belonge to Mayor Trummelschlager. Even today you can read in the birth register at Döllersheim that he and Josepha lived at number 13 in Strones.

And Georg and I are supposed to have owned other bits of furniture too, if you believe the Nazis:

‘In the Führer’s grandparents’ house there were some objects which, according to old people, were in their possession. This was established by the notary. These are 1 cupboard which was restored by Raffloer in Gars and set up in the house of the District Farmers’ Leader in Horn. But also in the possession of the Museum Association are – a spinning wheel at which the Führer’s grandmother used to spin, 1 distaff, 1 curling iron, one ox yoke, 1 trivet, 1 butter churn.’

And because a respectable newspaper once again illustrated the wardrobe as mine, and said, under the headline ‘The “Führer’s” grandmother and her exquisite furniture’, that the objects are only interesting today ‘because for want of other sources they provide us with information about the material situation and living conditions of Anna Maria Schicklgruber, Hitler’s grandmother,’ everyone believed all those fairy-tales. They wanted to turn me into an affluent kitchen-maid from the wealthy peasant class, and said:

‘Painted peasant wardrobes were an expensive rarity among the peasants of the Upper Waldviertel in the first third of the 19th century. Only a well-to-do peasant upper class could afford such luxury. But by no means would they be found in the possession of servants or cottage-dwellers. The rest of Hitler’s grandmother’s chattel suggest an established farming household.’

How right they were! No wonder. But the wardrobe and the household goods belonged not to me, but to a mayor. The fact that Georg and I had nothing left when I died was a thorn in the side for the Nazis. The new ‘Messiah’ simply shouldn’t have come from such poor conditions! But such was our poverty that I slept in the wooden cattle trough where the pastor ead me the last rites three days after New Year. After my corpse, all skin and bone, was laid out in a coffin at home, as is the custom hereabouts, so that neighbours and friends could pay their respects, I ended up in one of the paupers’ graves that used to lie at the steep end of the cemetery in Döllersheim. But I’m not alone here. My father, who died of consumption the November after my own death, is buried next to me, even though I would never have agreed to that in my lifetime. But I forgave him long ago.

No erected crosses to me in the churchyard, the people around here were too poor for that. Somebody would probably only have taken them for firewood anyway. And they wouldn’t have been any use to the dead in any case. So later no one knew the final resting place of my bones and skull. But of course no one could have guessed that as an insignificant cook I would play such an important part to play. Today I’m glad that I’ve found eternal rest at last. Because even the false grave with the crucifix and the mangled first name on the black slate panel, which read:

Here lies the grandmother of the Führer Maria A. Hitler, née Schicklgruber, b. 17.4.1795 in Strones, died 7.1.1847 in Kl. Motten’

and which those busy Nazis put up on the wall of the Döllersheim church in my honour during my grandson’s reign of terror was – thanks be to the Lord in all his infinite kindness – stolen at dead of night by people of the old school. They even got my date of birth wrong, those interfering ne’er-do-wells, and turned 15 April into 17 April, because they didn’t read the birth register correctly. But take care, they’re still at work! At Halloween I was amazed when the graves of my grandson’s relatives from Strones and Klein-Motten were decorated with white pebbles, flowers and burning candles. I’m just glad that no one in Döllersheim now remembers that I, the grandmother of a lunatic, am buried here. At the place where the cross stood in the Nazi era a metal laurel wreath was laid, and a sacred heart panel recalls the terrible murders in the camps for which I feel partly responsible. The terrible murders for which my own flesh and blood is responsible. The horrific work of my grandson Adolf, who has so many people on his conscience because he hated the Jews and imagined he belonged to a superior race. Even though he had the travelling people, the mentally retarded and the cripples killed because he couldn’t stand them, it was the Jews who troubled him the most. I alone know why! So ashamed of him am I that I could spin in my grave. In my filled-in crypt that no one knows, in the tranquil churchyard of Döllersheim, just like my memory, which I took with me beneath the ground.

They didn’t know much about me at all. Just that I had one child late in life. It was the only one I ever had. When I got pregnant I was still single. I had that child at the age of 42, Aloys. An ‘illegitimate’ child, a child of shame. The father of Adolf Hitler, in fact. How and where I, Anna Maria Schickelgruber, lived until I was 26, how my mother died, never interested anyone until now. I will have to warn you that I was not a good girl, I was a vicious, sinful woman. I’ve come to regret that most profoundly. But if one of the veils is to be lifted from my virginity now, it will probably be necessary to go further back and start with my birth, or even earlier than that.

Well then! Two years before I was born, my parents married. In this days it was still the custom to make an application of marriage, a contract that was to be drawn up and signed in Dietrichs, my mother’s birthplace. In this it said:

‘After Johann Schicklgruber son of Jakob Schicklgruber of the parish of Waldreichs subject of the manor of Strones and Theresia his wife both still living son born in wedlock, undertook to marry Theresia Pfeissingerin daughter of this manor subjects of Dietrichs and Gertraud his wife’s legitimate daughter; so between them in the presence of witnesses named hereafter and on the bridegroom’s side Joseph Schicklgruber of Strones and the bride’s side Lorenz Gletzel of the [SW1] mnr. of Dietrichs subject of Wetzlas also agree the following conditions, and joined in holy matrimony…’

And so on and so on.

My mother received from my grandmother a legacy of 100 gulden, and 200 gulden from my grandfather as a dowry, and furthermore a bed, a chest, a trousseau, a cow and 70 bushels of chaffed flax. This dowry was value over all at 355 gulden. My father, the bridegroom, also received, from his parents, 100 gulden and 200 additional gulden from their savings. In those days a cow cost around ten gulden, a breeding sow four and a bedstead with bedding about two gulden. It was further determined ‘that everything that they now bring together, and everything that they acquire or inherit during their marriage or are given by God’s rich bounty… will remain their common property’.

It was also agreed that in the event of their death, if there should be no biological inheritors, their nearest relatives were to receive a third of their property, but that if there were an inheritor, ‘friends’ would receive only half. So my parents were by no means as poor as I would later be.